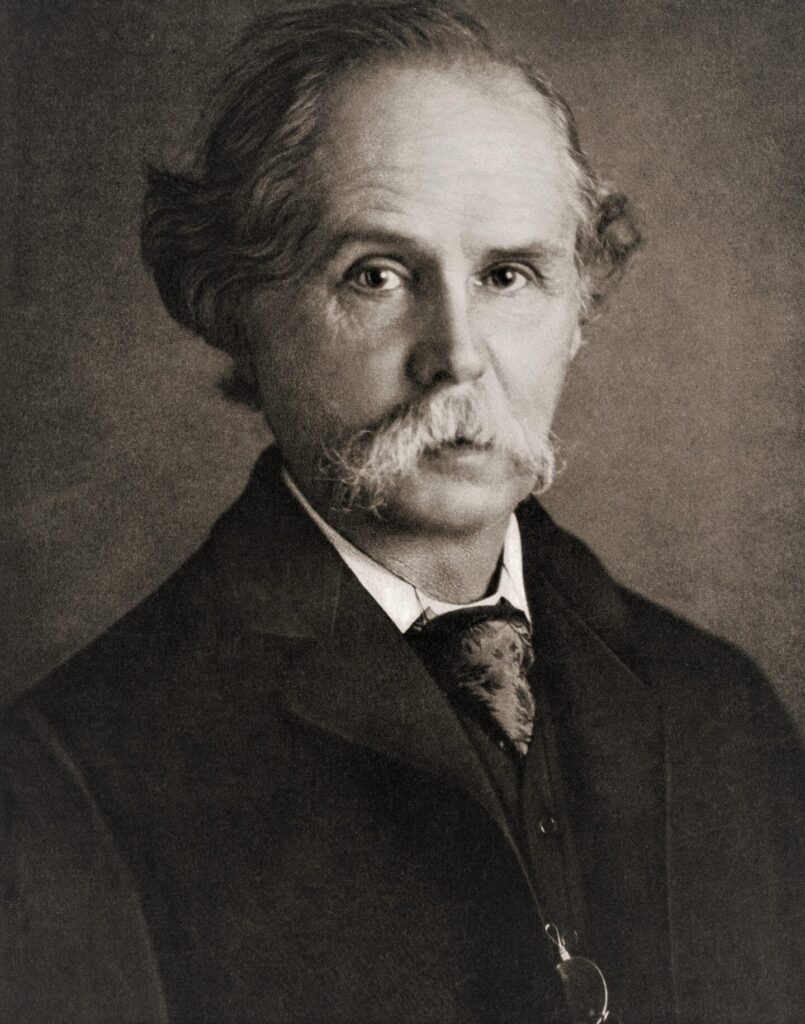

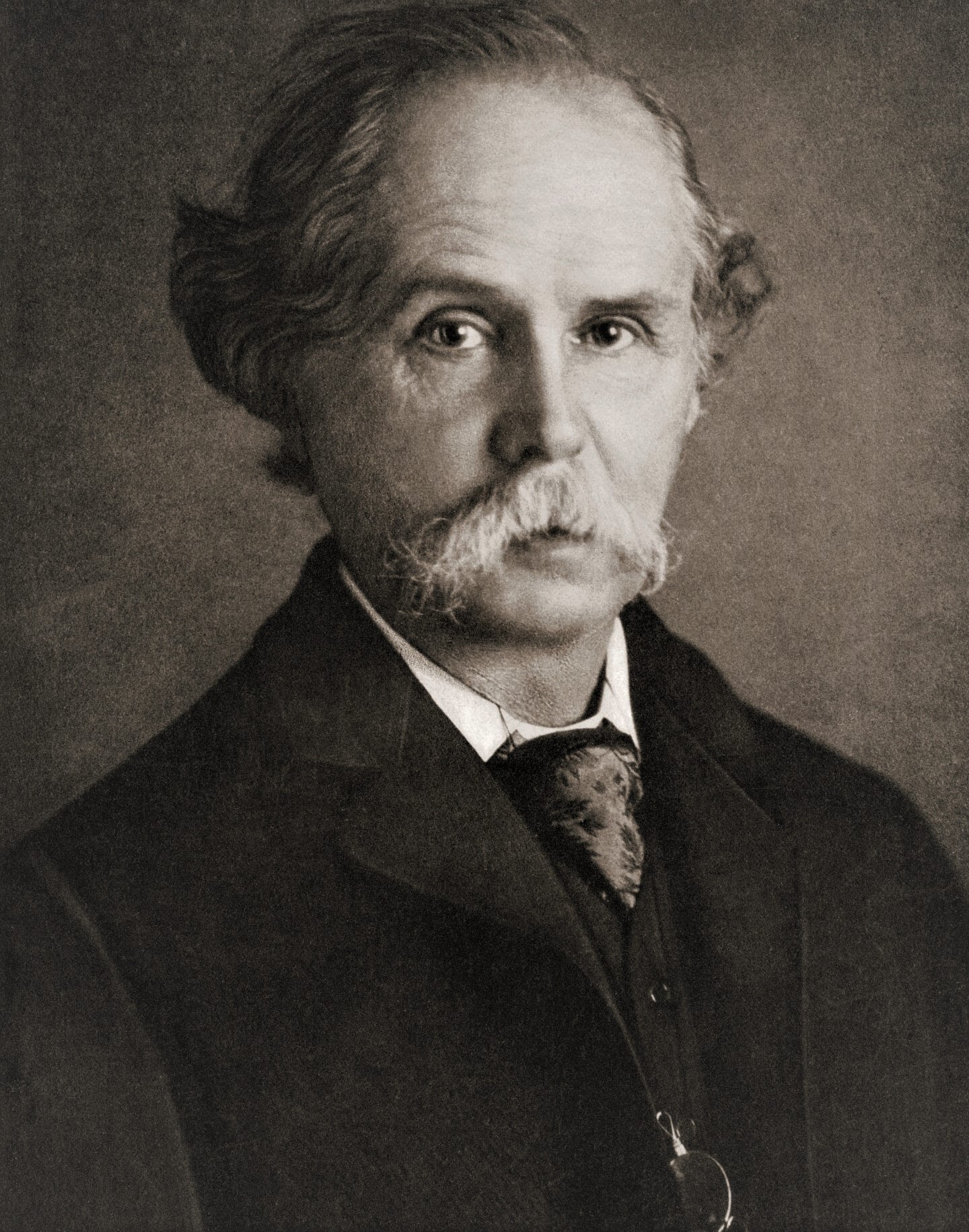

Economics Classical Definition by Alfred Marshall

- Marshall’s Welfare Definition:

Alfred Marshall emphasised human activities or human well-being rather than wealth in his book “Principles of Economics,” which was released in 1890. “A study of mankind as they live, move, and think in the daily business of life,” is how Marshall describes economics. He made the case that economics is a study of both man and wealth, on the one hand.

In Marshall’s own words, “Political Economy or Economics is a study of mankind in the ordinary business of life; it examines that part of individual and social action which is most closely connected with the attainment and with the use of the material requisites of well-being,” there is a clear emphasis on the welfare of people.

As a result, “Economics is, on the one hand, a study of wealth; and on the other, and more importantly, a portion of the study of mankind.” According to Marshall, wealth is a means to a goal—the aim of human welfare—rather than an end in and of itself, as was previously believed by classical authors.

The following crucial characteristics characterise this Marshallian definition:

i. Economics is a social science since it examines how people behave.

ii. Since it considers the ways in which people make and spend money, economics investigates the “everyday business of living.”

iii. Economics solely examines the “material” aspect of human welfare, which may be gauged using the unit of currency. Other human welfare endeavours that cannot be measured in monetary terms are neglected. In this regard, it is important to remember A. C. Pigou’s (1877–1959) definition—another outstanding neo-classical economist. Economics is “that aspect of social well-being that may be related to the yardstick of money either directly or indirectly.”

iv. “The nature and causes of the Wealth of Nations” are not the focus of economics. The goal of prime significance is the welfare of humanity, not the accumulation of money.

Criticisms:

Marshall’s concept of economics was criticised for a number of reasons, while being lauded as a revolutionary one.

i. Lionel Robbins (later Lord) (1898–1984) sharply criticised Marshall’s concept of “material well-being” in 1932. Robbins claimed that “non-material well-being” should be included in economics. It is hard to distinguish between material and non-material welfare in real life. The subject matter and scope of economics would be more limited if solely the “materialist” definition were to be adopted, or a significant portion of human economic activity would continue to fall beyond its purview.

ii. According to Robbins, Marshall was unable to show a connection between human economic activity and well-being. Different economic activity might have a negative impact on people’s welfare. The production of liquor, weaponry, and other commercial products does not advance the well-being of any community. These economic pursuits fall under the umbrella of economics.

iii. Marshall’s concept sought to quantify human welfare in monetary terms. However, because “welfare” is an ephemeral, personal idea, it cannot be measured. Money, in actuality, can never be a gauge of welfare.

iv.The “welfare definition” proposed by Marshall lends economics a moral bent. A normative science must make moral determinations. It must state if a specific economic activity is beneficial or detrimental. Robbins contends that value judgements must be avoided in economics. Ethics should evaluate values. Instead of being a normative science, economics is a positive science.

v. The essential issue of scarcity in every economy is ignored by Marshall’s formulation, to sum up. Robbins was the one who defined economics in terms of scarcity. Robbins described economics as the distribution of finite resources to meet insatiable human needs.